The Basics of Musical Structure

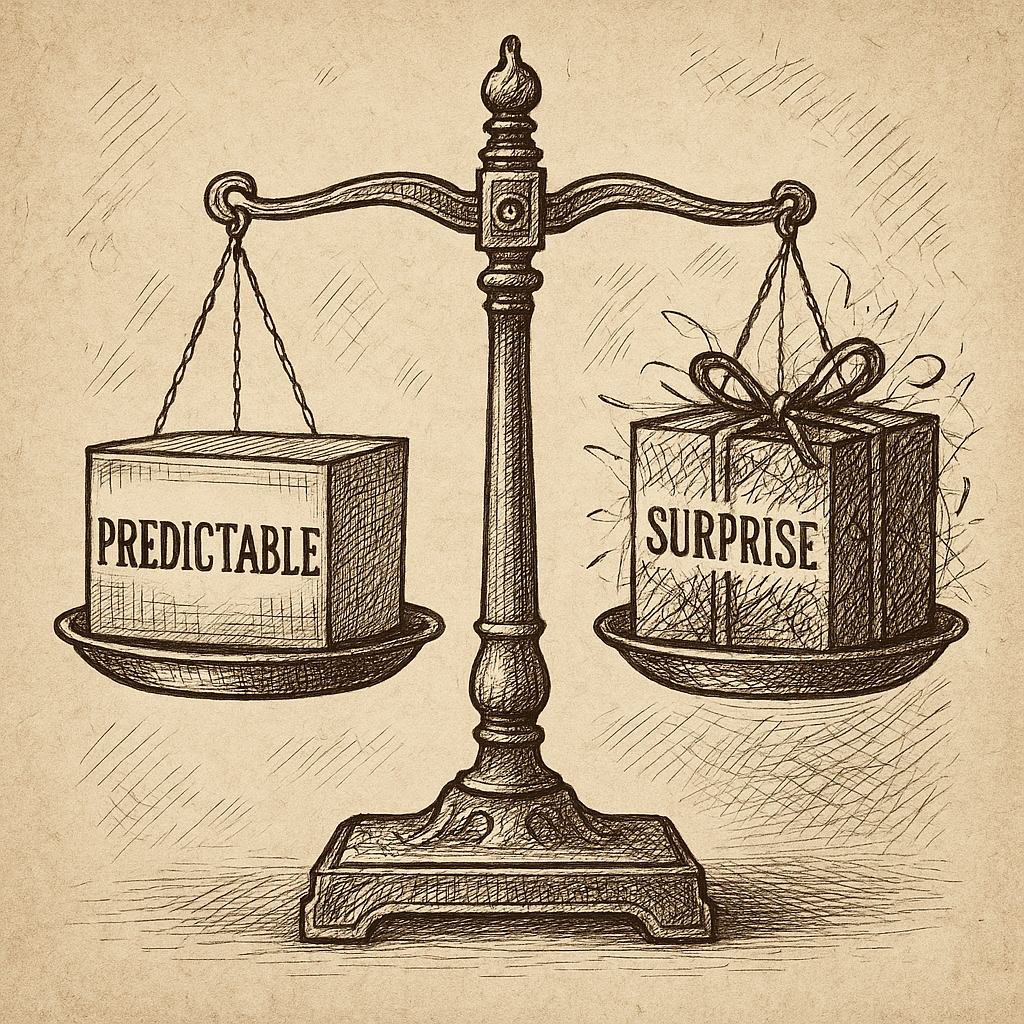

We like patterns with a twist. Music makes a game of that impulse: it’s a running negotiation between what you expect and what actually happens. Studies show that listeners gravitate to a “Goldilocks zone” of complexity—too predictable is dull; too chaotic, and we tune out—an elegant inverted‑U between certainty and surprise. In rhythm, that sweet spot often comes from mild syncopations that tease the beat without destroying it, the motor equivalent of a wink rather than a shove.

Structure is the set of promises a piece makes and (mostly) keeps. At the sentence level of music, cadences are punctuation marks: they signal “this thought is complete,” letting your ear file ideas before the next one arrives. Zoom out and you meet reliable maps. The 12‑bar blues is a three‑line, I–IV–V journey; because you know roughly where the harmony will go, the singer can bend notes and the guitarist can riff without losing you. Familiar road, fresh scenery. A larger map is sonata form—call it “home, away, home.” First the exposition lays out themes and a key; the development wanders and worries them; the recapitulation brings them back, now weathered but recognizably themselves.

Why does this balance feel so human? Mid‑century theorist Leonard Meyer argued that musical emotions arise when expectations are delayed, foiled, and finally resolved—like jokes whose punchlines arrive a beat late. David Huron’s “ITPRA” model updated the idea: we imagine what’s next, feel tension, predict, react, then appraise. Structure works by shaping each of those steps so the mind can learn while it listens.

Explained plainly: good pieces tell you enough to guess, then reward you for guessing almost right. That’s why the chorus you saw coming still thrills, the dropped beat still tickles, and the home key—when it finally returns—feels like the door clicking open after a long day.